In an earlier post, I raised a few issues with a large-scale RCT run in Bangladesh aimed at estimating the effectiveness of masks on reducing the spread of the coronavirus. In particular, I was a bit dismayed that the authors did not post the raw number of seropositive cases in their study, preventing me from computing standard statistical analyses of their results. I also objected to the number of statistical regressions run to pull signals out of a very complex intervention.

Recently, the authors were kind enough to release their code and data. I send nothing but kudos to them in this regard. Releasing code and data can help disambiguate questions that are not always answerable from papers alone. In fact, I was immediately able to answer my question by querying their data. In this post, I will walk through a simple analysis to estimate the efficacy of their proposed intervention.

In the Bangladesh Mask RCT, there were $n_C=$163,861 individuals from 300 villages in the control group. There were $n_T=$178,322 individuals from 300 villages in the intervention group. The main end point of the study was whether their intervention reduced the number of individuals who both reported covid-like symptoms and tested seropositive at some point during the trial. The number of such individuals appears nowhere in their paper, and one has to compute this from the data they kindly provided: There were $i_C=$1,106 symptomatic individuals confirmed seropositive in the control group and $i_T=$1,086 such individuals in the treatment group. The difference between the two groups was small: only 20 cases out of over 340,000 individuals over a span of 8 weeks.

I have a hard time going from these numbers to the assured conclusions that “masks work” that was promulgated by the media or the authors after this preprint appeared. This study was not blinded, as it’s impossible to blind a study on masks. The intervention was highly complex and included a mask promotion campaign and education about other mitigation measures including social distancing. Moreover, individuals were only added to the study if they consented to allow the researchers to visit and survey their household. There was a large differential between the control and treatment groups here, with 95% consenting in the treatment group but only 92% consenting in control. This differential alone could wash away the difference in observed cases. Finally, symptomatic seropositivity is a crude measure of covid as the individuals could have been infected before the trial began.

Given the numerous caveats and confounders, the study still only found a tiny effect size. My takeaway is that a complex intervention including an educational program, free masks, encouraged mask wearing, and surveillance in a poor country with low population immunity and no vaccination showed at best modest reduction in infection. I think this summary is fair to the study authors. And this is valuable information to have! It reaffirms my priors that non-pharmaceutical interventions are challenging to implement and have only modest benefits in the presence of a highly contagious respiratory infection. But your mileage may vary.

As I mentioned, of course, this was not the message that the majority of the media took away from this study. Instead we were told that this trial finally confirmed that masks worked. I think one of the key confusing points was using “efficacy” instead of relative risk as a measure of intervention power.

One of the dark tricks of biostatistics is moving away from absolute case counts to measures of risk such as relative risk reduction, efficacy, or the odds ratio. All of these measures are relative, and they tend to exaggerate effects. The relative risk reduction is the ratio of the rate of infection in the treatment group to the rate of infection in the control group

\[{\small RR = \frac{i_T/n_T}{i_C/n_C}\,. }\]A small $RR$ corresponds to a large reduction in risk. For the mask study, $RR=$0.9. That’s not a lot of risk reduction: in this study, community masking improved an individual’s risk of infection by a factor of only 1.1x. As a convenient comparator, the $RR$ in the MRNA vaccine trials was 0.05. In this case, vaccines reduce the risk of symptomatic infection by a factor of 20x.

The academic vaccine community unfortunately uses “efficacy” or “effectiveness” to describe relative risk reduction. Efficacy is a confusing, commonly misinterpreted metric. Efficacy in a trial is one minus the relative risk reduction:

\[{\small EFF = 1-RR\,, }\]reported as a percentage. So if the $RR=$0.9, then $EFF=$10%.

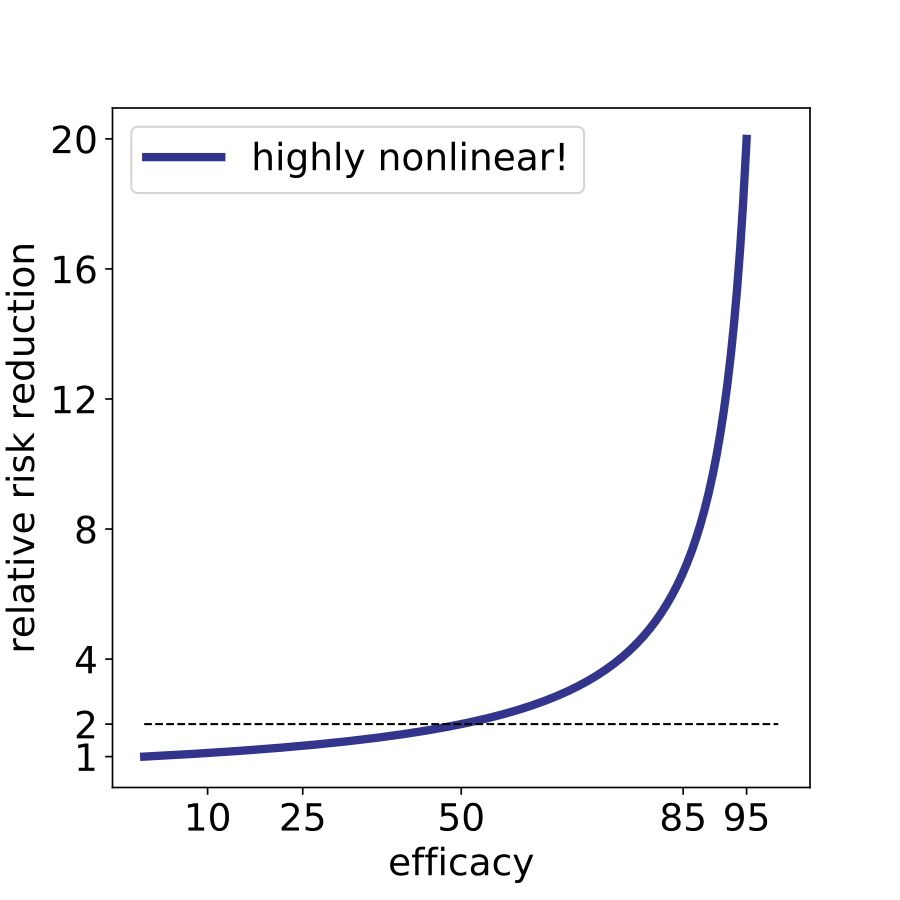

The important thing to realize about efficacy is that the range from 0% to 20% is barely better than nothing. Here, even a 20% efficacy corresponds to a reduction of risk by a factor of 1.25x. 1.25x is not literally nothing, but it’s also not enough to halt a highly contagious respiratory infection. For what it’s worth, a vaccine with 20% efficacy would not be approved. Another major flaw of using efficacy as a metric is that it is highly nonlinear. The difference between 10% and 20% efficacy is very small whereas the difference between 85% and 95% is huge, corresponding to a 7-fold and 20-fold risk reduction respectively. Efficacy is a nonlinear metric, but these percentages are bandied around as if they are linear effects, and this adds confusion to the public dialogue.

To further dive into the absurdity of efficacy, let’s examine the claim that “cloth masks” worked less well than “surgical masks.” This is too strong an observation to be gleaned from the data. The preprint provides two stratified calculations to estimate the efficacy of types of masks. In the first case, the authors analyzed villages randomized to only be given surgical masks and their matched control villages. In this case there were 190 pairs of villages consisting of $n_C=$103,247 individuals in the control group and $n_T=$113,082 individuals in the treatment group. They observed $i_C=$774 symptomatic and seropositive individuals in the control group and $i_T=$756 symptomatic and seropositive individuals in the treatment group. This is a difference of 18 individuals. The corresponding efficacy is 11%, still woefully low.

We can do a similar analysis for the villages only given cloth masks. There were 96 pairs of villages consisting of $n_C=$53,691 individuals in the control group and $n_T=$57,415 individuals in the treatment group. They observed $i_C=$332 symptomatic and seropositive individuals in the control group and $i_T=$330 symptomatic and seropositive individuals in the treatment group. This is a difference of only 2 individuals. Certainly, no one would put much faith in an intervention where we see a difference of 2 cases in a study with over one hundred thousand people. However, to further demonstrate the absurdity of the notion of efficacy, the observed efficacy for cloth masks in this study is 7%. I think in many people’s minds, the difference between 7% and 11% is small. And 7% should be considered “no effect” as should 11%. As a final absurd comparison, the study data shows cloth masks are more efficacious than purple surgical masks where the estimated efficacy is 0% ($n_C=$27,918, $n_T=$29,541, $i_C=$177, $i_T=$187)! (Ed note: turns out the purple masks were cloth. So the cloth purple masks did nothing, but the red masks “work.” Indeed, red masks were more effective than surgical masks!) Certainly, comparing a bunch of such small effects is not telling us much.

Anyone who spends too much time around statisticians will note that I never once tried to compute a p-value for any of these results. As I’ve belabored, obsession with statistical significance distracts us from discussing effect sizes. We should be able to just look at the effect size and conclude the study did not find a significant impact of masks on coronavirus spread. We don’t need a p-value to tell us 10% efficacy is not helpful in this context. But it’s also important to note that you can’t just run a standard binomial test on this data because it is cluster-randomized and the subjects are anything but independent. In the next blog, just for the sake of academic navel gazing, I’ll discuss the lack of statistical significance of this study and show why cluster randomized trials are inherently more challenging to interpret than standard RCTs.