In the last post, we showed that continuous-time LQR has “natural robustness” insofar as the optimal solution is robust to a variety of model-mismatch conditions. LQR makes the assumption that the state of the system is fully, perfectly observed. In many situations, we don’t have access to such perfect state information. What changes?

The generalization of LQR to the case with imperfect state observation is called “Linear Quadratic Gaussian” control (LQG). This is the simplest, special case of a Partially Observed Markov Decision Process (POMDP). We again assume linear dynamics:

\[\dot{x}_t = Ax_t + B u_t + w_t\,.\]where the state is now corrupted by zero-mean Gaussian noise, $w_t$. Instead of measuring the state $x_t$ directly, we instead measure a signal $y_t$ of the form

\[y_t = C x_t + v_t\,.\]Here, $v_t$ is also zero-mean Gaussian noise. Suppose we’d still like to minimize a quadratic cost function

\[\lim_{T\rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{T} \int_{0}^{T} (x_t^\top Qx_t + u_t^\top Ru_t) dt\,.\]This problem is very similar to our LQR problem except for the fact that we get an indirect measurement of the state and need to apply some sort of filtering of the $y_t$ signal to estimate $x_t$.

The optimal solution for LQG is strikingly elegant. Since the observation of $x_t$ is through a Gaussian process, the maximum likelihood estimation algorithm has a clean, closed form solution, even in continuous time. Our best estimate for $x_t$, denoted $\hat{x}_t$, given all of the data observed up to time $t$ obeys a differential equation

\[\frac{d\hat{x}}{dt} = A\hat{x}_t + B u_t + L(y_t-C\hat{x}_t)\,.\]The matrix $L$ that can be found by solving an algebraic Riccati equation that depends on the variance of $v_t$ and $w_t$ and on the matrices $A$ and $C$. In particular, it’s the CARE with data $(A^\top,C^\top,\Sigma_w,\Sigma_v)$. This solution is called a Kalman Filter and is a continuous limit of the discrete time Kalman Filter one might see in a course on graphical models.

The optimal LQG solution takes the estimate of the Kalman Filter, $\hat{x}_t$, and sets the control signal to be

\[u_t = -K\hat{x}_t\,.\]Here, $K$ is gain matrix that would be used to solve the LQR problem with data $(A,B,Q,R)$. That is, LQG performs optimal filtering to compute the best state estimate, and then computes a feedback policy as if this estimate was a noiseless measurement of the state. That this turns out to be optimal is one of the more amazing results in control theory. It decouples the process of designing an optimal filter from designing an optimal controller, enabling simplicity and modularity in control design. This decoupling where we treat the output of our state estimator as the true state is an example of certainty equivalence, the umbrella term for using point estimates of stochastic quantities as if they were the correct value. Though certainty equivalent control may be suboptimal in general, it remains ubiquitous for all of the benefits it brings as a design paradigm. Unfortunately, not only is this decoupled design of filters and controllers often suboptimal, it has many hidden fragilities. LQG highlights a particular scenario where certainty equivalent control leads to misplaced optimism about robustness.

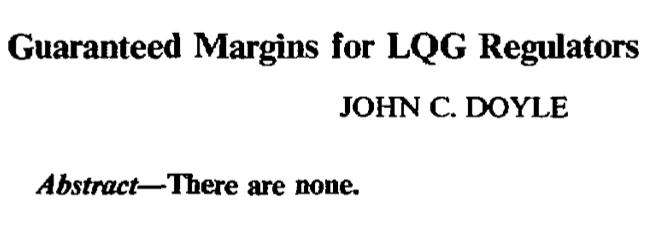

We saw in the previous post that LQR had this amazing robustness property: even if you optimize with the wrong model, you’ll still probably be OK. Is the same true about LQG? What are the guaranteed stability margins for LQG regulators? The answer was succinctly summed up in the abstract of a 1978 paper by John Doyle: “There are none.”

What goes wrong? Doyle came up with a simple counterexample, that I’m going to simplify even further for the purpose of contextualizing in our modern discussion. Before presenting the example, let’s first dive into why LQG is likely less robust than LQR. Let’s assume that the true dynamics obeys the ODE:

\[\dot{x}_t = Ax_t + B_\star u_t + w_t \,,\]though we computed the optimal controller with the matrix $B$. Define an error signal, $e_t = x_t - \hat{x}_t$, that measures the current deviation between the actual state and the estimate. Then, using the fact that $u_t = -K \hat{x}_t$, we get the closed loop dynamics

\[\small \frac{d}{dt} \begin{bmatrix} \hat{x}_t\\ e_t \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} A-BK & LC\\ (B-B_\star) K & A-LC \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} \hat{x}_t\\ e_t \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} Lv_t\\ w_t-Lv_t \end{bmatrix}\,.\]When $B=B_\star$, the bottom left block is equal to zero. The system is then stable provided $A-BK$ and $A-LC$ are both stable matrices (i.e., have eigenvalues in the left half plane). However, small perturbations in the off-diagonal block can make the matrix unstable. For intuition, consider the matrix

\[\begin{bmatrix} -1 & 200\\ 0 & -2 \end{bmatrix}\,.\]The eigenvalues of this matrix are $-1$ and $-2$, so the matrix is clearly stable. But the matrix

\[\begin{bmatrix} -1 & 200\\ t & -2 \end{bmatrix}\]has an eigenvalue greater than zero if $t>0.01$. So a tiny perturbation significantly shifts the eigenvalues and makes the matrix unstable.

Similar things happen in LQG. In Doyle’s example he uses the problem instance:

\[A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1\\ 0 & 1\end{bmatrix} \,,~~~ B = \begin{bmatrix} 0\\1 \end{bmatrix}\,, ~~~ C= \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0\end{bmatrix}\] \[Q = \begin{bmatrix} 5 & 5 \\ 5 & 5 \end{bmatrix} \,, ~~~ R = 1\] \[\mathbb{E}\left[w_t w_t^\top\right]=\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1\end{bmatrix} \,,~~~ \mathbb{E}\left[v_t^2\right]=\sigma^2\]The open loop system here is unstable, having two eigenvalues at $1$. We can stabilize the system only by modifying the second state. The state disturbance is aligned along the $[1;1]$ direction, and the state cost only penalizes states aligned with this disturbance. So the goal is simply to remove as much signal as possible in the $[1;1]$ direction without using too much control authority. We only are able to measure the first component of the state, and this measurement is corrupted by Gaussian noise.

What does the optimal policy look like? Perhaps unsurprisingly, it focuses all of its energy on ensuring that there is little state signal along the disturbance direction. The optimal $K$ and $L$ matrices are

\[K = \begin{bmatrix} 5 & 5 \end{bmatrix}\,,~~~L=\begin{bmatrix} d\\ d \end{bmatrix}\,,~~~d:=2+\sqrt{4+\sigma^{-2}}\,.\]Now what happens when we have model mismatch? If we set $B_\star=tB$ and use the formula for the closed loop above, we see that closed loop state transition matrix is

\[\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 & d & 0\\ -5 & -4 & d & 0\\ 0 & 0 &1-d &1\\ 4(1-t) & 4(1-t) & -d &1 \end{bmatrix}\,.\]It’s straight forward to check that when $t=1$ (i.e., no model mismatch), the eigenvalues of $A-BK$ and $A-LC$ all have negative real parts. For the full closed loop matrix, analytically computing the eigenvalues themselves is a pain, but we can prove instability by looking at the characteristic polynomial. For a matrix to have all of its eigenvalues in the left half plane, its characteristic polynomial necessarily must have all positive coefficients. If we look at the linear term in the polynomial, we see that we must have

\[t < 1 + \frac{1}{5d}\]if we’d like any hope of having a stable system. Hence, we can guarantee that this closed loop system is unstable if $t\geq 1+\sigma$. This is a very conservative condition, and we could get a tighter bound if we’d like, but it’s good enough to reveal some paradoxical properties of LQG. The most striking is that if we build a sensor that gives us a better and better measurement, our system becomes more and more fragile to perturbation and model mismatch. For machine learning scientists, this seems to go against all of our training. How can a system become less robust if we improve our sensing and estimation?

Let’s look at the example in more detail to get some intuition for what’s happening. When the sensor noise gets small, the optimal Kalman Filter is more aggressive. If the model is true, then the disturbance has equal value in both states, so, when $\sigma$ is small, the filter can effectively just set the value of the second state to be equal to whatever is in the first state. The filter is effectively deciding that the first state should equal the observation $y_t$, and the second state should be equal to the first state. In other words, it rapidly damps any errors in the disturbance direction $[1;1]$ and, as $d$ increases, it damps the $[0;1]$ direction less. When $t \neq 1$, we are effectively introducing a disturbance that makes the two states unequal. That is, $B-B_\star$ is aligned in the $[0;1]$ and can be treated as a disturbance signal. This undamped component of the error is fed errors from the state estimate $\hat{x}$, and these errors compound each other. Since we spend so much time focusing on our control along the direction of the injected state noise, we become highly susceptible to errors in a different direction and these are the exact errors that occur when there is a gain mismatch between the model and reality.

The fragility of LQG has many takeaways. It highlights that noiseless state measurement can be a dangerous modeling assumption, because it is then optimal to trust our model too much. Though we apparently got a freebie with LQR, for LQG, model mismatch must be explicitly accounted for when designing the controller.

This should be a cautionary tale for modern AI systems. Most of the papers I read in reinforcement learning consider MDPs where we get perfect state measurement. Building an entire field around optimal actions with perfect state observation builds too much optimism. Any realistic scenario is going to have partial state observation, and such problems are much thornier.

A second lesson is that it is not enough to just improve the prediction components in feedback systems that are powered by machine learning. I have spoken with many applied machine learning engineers who have told me that they have seen performance degrade in production systems when they improve their prediction model. They might spend months building some state of the art LSTM mumbo jumbo that is orders of magnitude more accurate in prediction, but in production yields worse performance than the legacy system with a boring ARMA model. It is quite possible that these performance drops are due to the Doyle effect: the improved prediction system is increasing sensitivity to a modeling flaw in some other part of the engineering pipeline.

The story turns out to be even worse than what I have described thus far. The supposed robustness guarantees we derived for LQR assume not just full noiseless state measurement, but that the sensors and actuators have infinite bandwidth. That is, they assume you can build controllers $K$ with arbitrarily large entries and that react instantaneously, without delay, to changes in the state. In the next post, I’ll show how realistic sampled data controllers for LQR, even with noiseless state measurement, also have no guarantees.