This is the ninth part of “An Outsider’s Tour of Reinforcement Learning.” Part 10 is here. Part 8 is here. Part 1 is here.

Before we leave these model-free chronicles behind, let me turn to the converse of the Linearization Principle. We have seen that random search works well on simple linear problems and appears better than some RL methods like policy gradient. Does random search break down as we move to harder problems? Spoiler Alert: No. But keep reading!

Let’s apply random search to problems that are of interest to the RL community. The deep RL community has been spending a lot of time and energy on a suite of benchmarks, maintained by OpenAI and based on the MuJoCo simulator. Here, the optimal control problem is to get the simulation of a legged robot to walk as far and quickly as possible in one direction. Some of the tasks are very simple, but some are quite difficult like the complicated humanoid models with 22 degrees of freedom. The dynamics of legged robots are well-specified by Hamiltonian Equations, but planning locomotion from these models is challenging because it is not clear how to best design the objective function and because the model is piecewise linear. The model changes whenever part of the robot comes into contact with a solid object, and hence a normal force is introduced that was not previously acting upon the robot. Hence, getting robots to work without having to deal with complicated nonconvex nonlinear models seems like a solid and interesting challenge for the RL paradigm.

Recently, Salimans and his collaborators at Open AI showed that random search worked quite well on these benchmarks. In particular, they fit neural network controllers using random search with a few algorithmic enhancements (They call their version of random search “Evolution Strategies,” but I’m sticking with my naming convention). In another piece of great work, Rajeswaran et al showed that Natural Policy Gradient could learn linear policies that could complete these benchmarks. That is, they showed that static linear state feedback, like the kind we use in LQR, was also sufficient to control these complex robotic simulators. This of course left an open question: can simple random search find linear controllers for these MuJoCo tasks?

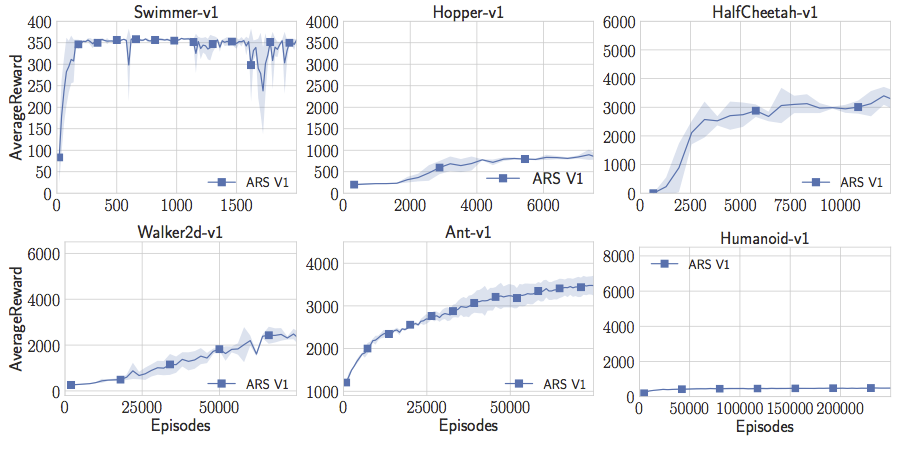

My students Aurelia Guy and Horia Mania tested this out, coding up a rather simple version of random search (the one from lqrpols.py in my previous posts). Surprisingly (or not surprisingly), this simple algorithm learns linear policies for the Swimmer-v1, Hopper-v1, HalfCheetah-v1, Walker2d-v1, and Ant-v1 tasks that achieve the reward thresholds previously proposed in the literature. Not bad!

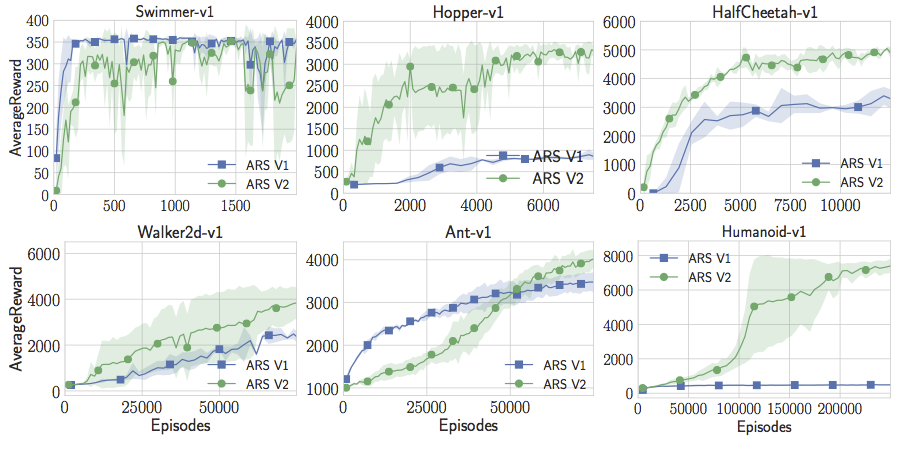

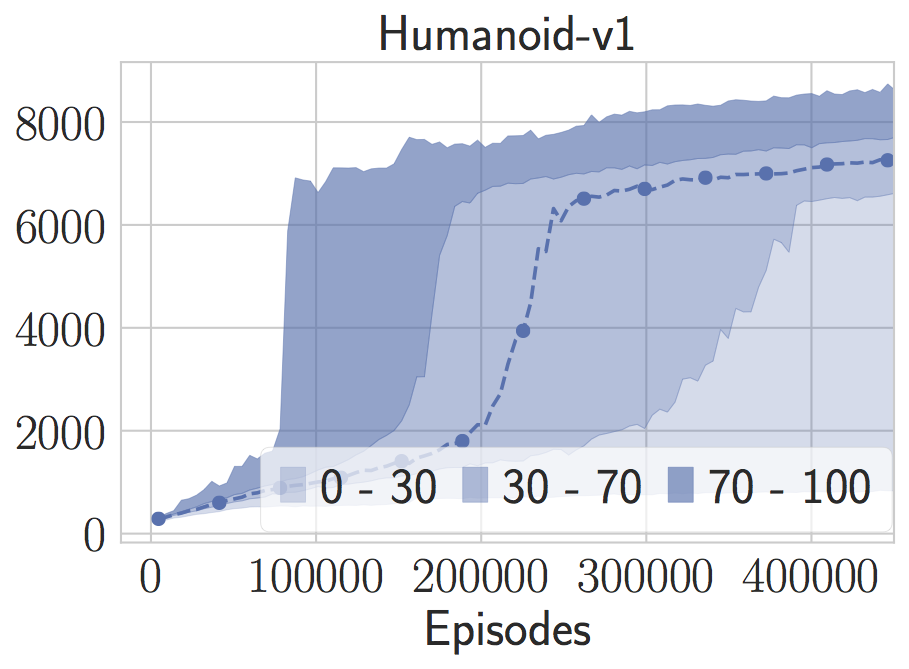

But random search alone isn’t perfect. Aurelia and Horia couldn’t get the humanoid model to do anything interesting at all. Having tried a lot of parameter settings, they decided to try to enhance random search to get it to train faster. Horia noticed that a lot of the RL papers were using statistics of the states and whitening the states before passing them into the neural net that defined the mapping from state to action. So he started to keep online estimates of the states and whiten them before passing them to the linear controller. And voila! With this simple trick, Aurelia and Horia now get state-of-the-art performance on Humanoid. Indeed, they can reach rewards over 11000 which is higher than anything I’ve seen reported. It is indeed almost twice the “success threshold” that was used for benchmarking by Salimans et al. Linear controller. Random search. One simple trick.

What’s nice about having something this simple is that the code is 15x faster than what is reported in the OpenAI Evolution Strategies paper. We can obtain higher rewards with less computation. One can train a high performing humanoid model in under an hour on a standard EC2 instance with 18 cores.

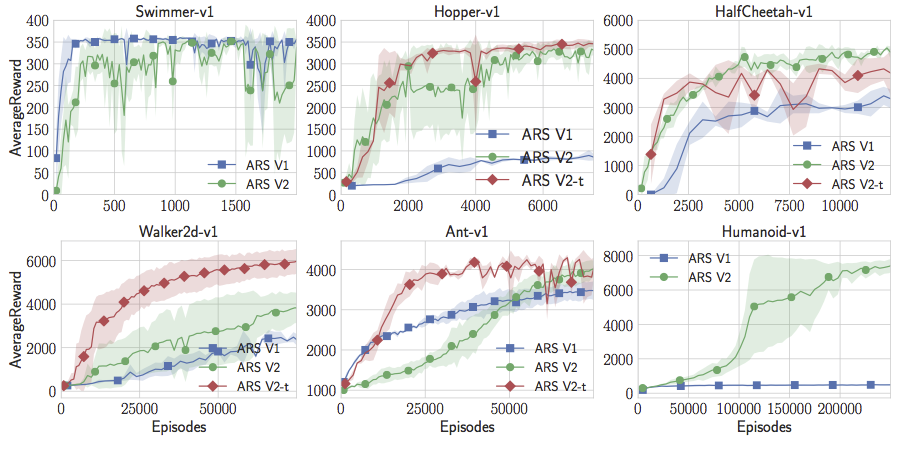

Now, with the online state updating, random search not only exceeds state-of-the-art on Humanoid, but also on Swimmer-v1, Hopper-v1, HalfCheetah-v1. But it isn’t yet as good on Walker2d-v1 and Ant-v1. But we can add one more trick to the mix. We can drop the sampled directions that don’t yield good rewards. This adds a hyperparameter (which fraction of directions to keep), but with this one additional tweak, random search can actually match or exceed the state-of-the-art performance of all of the MuJoCo baselines in the OpenAI gym. Note here, I am not restricting comparisons to policy gradient. As far as I know from our literature search, these policies are better than any results that apply model-free RL to the problem, whether it be an Actor Critic Method, a Value Function Estimation Method, or something even more esoteric. It does seem like pure random search is better than deep RL and neural nets for these MuJoCo problems.

Random search with a few minor tweaks outperforms all other methods on these MuJoCo tasks and is significantly faster. We have a full paper with these results and more here. And our code is in this repo, though it is certainly easy enough to code up for yourself.

What can reinforcement learning learn from random search?

There are a few of important takeaways here.

Benchmarks are hard.

I think the only reasonable conclusion from all of this is that these MuJoCo demos are easy. There is nothing wrong with that. But it’s probably not worth deciding NIPS, ICML, or ICLR papers over performance on these benchmarks anymore. This does leave open a very important question: what makes a good benchmark for RL?. Obviously, we need more than the Mountain Car. I’d argue that LQR with unknown dynamics is a reasonable task to master as it is easy to specify new instances and easy to understand the limits of achievable performance. But the community should devote more time to understanding how to establish baselines and benchmarks that are not easily gamed.

Never put too much faith in your simulators.

Part of the reason why these benchmarks are easy is that MuJoCo is not a perfect simulator. MuJoCo is blazingly fast, and is great for proofs of concept. But in order to be fast, it has to do some smoothing around the contacts (remember, discontinuity at contacts is what makes legged locomotion hard). Hence, just because you can get one of these simulators to walk, doesn’t mean that you can get an actual robot to walk. Indeed, here are four gaits that achieve the magic 6000 threshold. None of these look particularly realistic:

even the top performing model (reward 11,600) looks like a very goofy gait that might not work in reality:

Strive for algorithmic simplicity.

Adding hyperparameters and algorithmic widgets to simple algorithms can always improve their performance on a small enough set of benchmarks. I don’t know if dropping top-performing directions or state normalization will work on a new random search problem, but it worked for these MuJoCo benchmarks. Higher rewards might even be achieved by adding more adding tunable parameters. If you add enough bells and whistles, you can probably convince yourself that any algorithm works for a small enough set of benchmarks.

Explore before you exploit.

Note that since our random search method is fast, we can evaluate its performance on many random seeds. These model-free methods all exhibit alarmingly high variance on these benchmarks. For instance, on the humanoid task, the the model is slow to train almost a quarter of the time even when supplied with what we thought were good parameters. And for those random seeds it finds rather peculiar gaits. It’s often very misleading to restrict one’s attention to 3 random seeds for random search, because you may be tuning your performance to peculiarities of the random number generator.

This sort of behavior arose in LQR as well. We can tune our algorithm for a few random seeds, and then see completely different behavior on new random seeds. Henderson and et observed this phenomenon already with Deep RL methods, but I think that such high variability will be a symptom of all model-free methods. There are simply too many edge cases to account for through simulation alone. As I said in the last post: “By throwing away models and knowledge, it is never clear if we can learn enough from a few instances and random seeds to generalize.”

I can’t quit model-free RL.

In a future post, I’ll have one more nit to pick with model-free RL. This is actually a nit I’d like to pick with all of reinforcement learning and iterative learning control: what exactly do we mean by “sample complexity?” What are we learning as a community from this line of research of trying to minimize sample complexity on a small number of benchmarks? And where do we, as a research community, go from here?

Before we get there though, let me take a step back to assess some variants of model-free RL that both work well in theory and practice and see if these can be extended to the more challenging problems currently of interest to the machine learning community.