This is the eighth part of “An Outsider’s Tour of Reinforcement Learning.” Part 9 is here. Part 7 is here. Part 1 is here.

I’ve been swamped with a bit of a travel binge and am hopelessly behind on blogging. But I have updates! This should tide us over until next week.

After my last post on nominal control, I received an email from Pavel Christof pointing out that if we switch from stochastic gradient descent to Adam, policy gradient works much better. Indeed, I implemented this myself, and he’s totally right. Let’s revisit the last post with a revised Jupyter notebook.

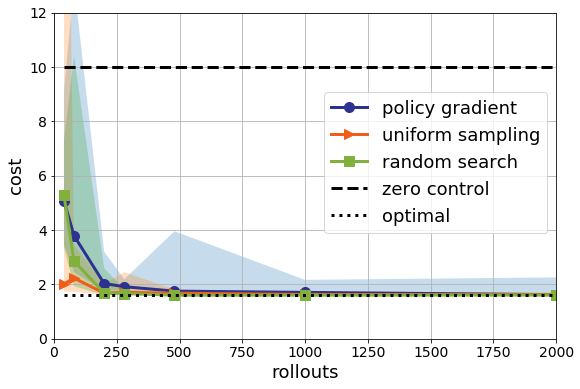

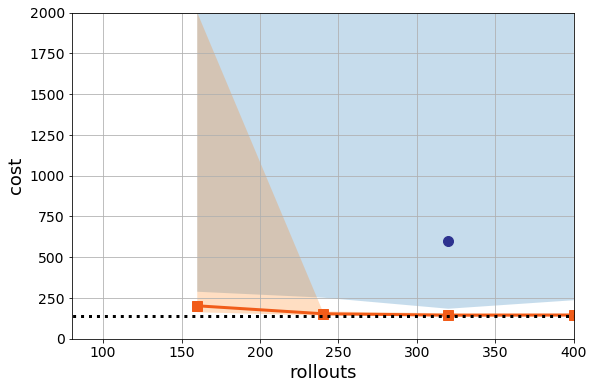

First, I coded up Adam in pure python to avoid introducing any deep learning package dependencies (it’s only 4 lines of python, after all). Second, I also fixed a minor bug in my random search code which improperly scaled the search direction. Now if we look again at the median performance, we see this:

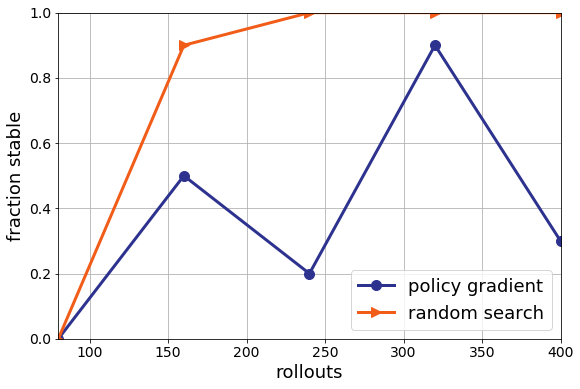

Policy gradient looks a lot better! It’s still not as good as pure random search, but it’s close. And, as Pavel pointed out, we can remove the annoying “clipping” to the $[-2,2]$ hypercube I needed to get Policy Gradient to appear to converge. Of course, both are still worse than uniform sampling and orders of magnitude worse than nominal control. On the infinite time horizon, the picture is similar:

Policy gradient still hiccups with some probability, but is on average only a bit worse than random search at extrapolation.

This is great. Policy gradient can be fixed on this instance of LQR by using Adam, and it’s not quite as egregious as my notebook made it look. Though it’s still not competitive with a model-based method for this simple problem.

For what it’s worth, neither Pavel or I could get standard gradient descent to converge for this problem. If any of you can get ordinary SGD to work, please let me know!

Despite this positive development, I have to say I remain discomforted. I have been told by multiple people that Policy Gradient is a strawman, and we need to add heuristics for baselines and special solvers on top of the original estimator to make it work. But if that is true, why do we still do worse than pure random search? Perhaps adding more to the problem can improve performance: maybe a trust-region with inexact CG solve, or value function estimation (we’ll explore this in a future post). But the more parameters we add, the more we can just overfit to this simple example.

I do worry a lot in ML in general that we deceive ourselves when we add algorithmic complexity on a small set of benchmark instances. As an illustrative example, let’s now move to a considerably harder instance of LQR. Let’s go from idealized quadrotor models to idealized datacenter models, as everyone knows that RL is the go-to approach for datacenter cooling. Here’s a very rough linear model of a collection of three server racks each with their own cooling devices:

Each component of the state $x$ is the internal temperature of one of the racks, and their traffic causes them to heat up with a constant load. They also shed heat to their neighbors. The control enables local cooling. This gives a linear model

\[x_{t+1} = Ax_t + Bu_t+w_t\]Where

\[A = \begin{bmatrix} 1.01 & 0.01 & 0\\ 0.01 & 1.01 & 0.01 \\ 0 & 0.01 & 1.01 \end{bmatrix} \qquad \qquad B = I\]This is a toy, but it’s instructive. Let’s try to solve the LQR problem with the settings $Q = I$ and $R= 1000 I$. This models trying hard to minimize the power consumption of the fans but still keeping the data center relatively cool. Now what happens for our RL methods on this instance?

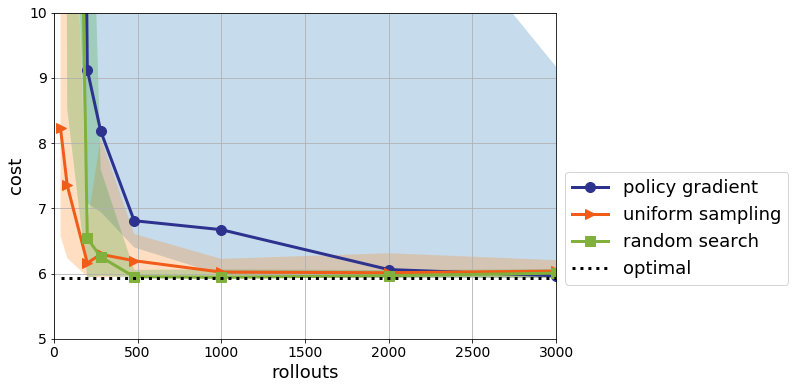

I tuned the parameters of Adam (even though I am told that Adam never needs tuning), and this is the best I can get:

You might be able to tune this better than me, and I’d encourage you to try (python notebook for the intrepid). Again, I would love feedback here as I’m trying to learn the ins and outs of the space as much as everyone reading this.

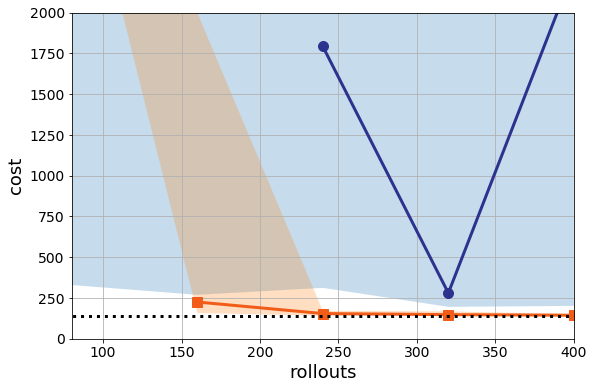

What is more worrying to me is that if I change the random seed to 1336 but keep the parameters the same, the performance degrades for PG:

That means that we’re still very much in a very high variance regime for Policy Gradient.

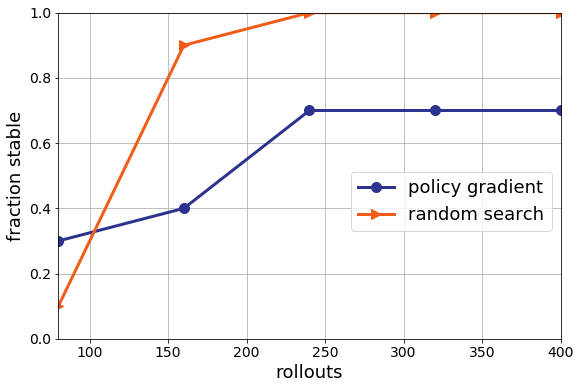

Now note, even though random search is better than policy gradient here, random search is still really bad. It is still finding many unstable solutions on this harder instance. That’s certainly less than ideal. Even if random search is better than deep RL, I probably wouldn’t use it in my datacenter. This for me is the main point. We can tune model-free methods all we want, but, I think there are fundamental limitations to this methodology. By throwing away models and knowledge, it is never clear if we can learn enough from a few instances and random seeds to generalize. I revisit this on considerably more challenging problems in the next post.

What makes this example hard? In order to understand the hardness, we have to understand the instance. The underlying dynamics are unstable. This means, unless a proper control is applied, the system will blow up (and the servers will catch fire). If you look at the last line of the notebook, you’ll see that even the nominal controller is producing an unstable solution with one rollout. This makes sense: if we estimate one of the diagonal entries of $A$ to be less than $1$, we might guess that this mode is stable and put less effort to cooling that rack. So it’s imperative to get a high quality estimate of the system’s true behavior for near optimal control. Or rather, we have to be able to ascertain whether or not our current policy is safe or the consequences can be disastrous. Though this series seems to be ever-expanding, an important topic of a future post is how to tightly link in safety and robustness concerns when learning to control.