While intricate deep models are all the rage in machine learning, my last post tried to make the case that we still need to care about model regularization. As it has been since the dawn of time, choosing simple models is still our best weapon against overfitting. But what does “simple” mean exactly? Of the many ways to measure simplicity, I’ve always been partial to the “minimum description length” principle: the fewer lines of code needed to train, store, and evaluate your model, the more robust that model likely is.

Unfortunately, there aren’t numerical methods that reliably compute models of minimum description length. You can’t just add a penalty to your loss in tensorflow and run stochastic gradient descent to automatically shorten your code (or can you? I know I just gave some of you terrible ideas). So what to do when algorithms fail you? Of course, the answer must be to turn to the crowd! My graduate student Ross Boczar recently wrote up a very fun long read on his recent forays into crowd-sourcing tiny machine learning models, and I think he has stumbled upon an infallible methodology for generating minimal models.

Some background: here at Berkeley, some passionate educators have launched an impressive new course, STAT/CS C8, aimed at teaching the core of data science in a way that is accessible to all majors. The course combines much of what you would learn in their first computer science course with projects and concepts based in statistics. It is part of an ambitious push by Berkeley to bring computation to all of the disciplines.

The final project for the course in Fall of 2015 was song genre classification. The students were given an array of word frequencies with corresponding genres–each song was labeled either “Hip-hop” or “Country”. Ross was one of the TAs for the course, and he organized a mini-competition for the students against the TAs: the students’ goal was to create the best possible classifier using any technique. The classifiers would be evaluated on an unseen (to both the staff and the students) holdout set. The student with the highest prediction accuracy on the holdout set would then be declared the winner.

In order to create an appropriate handicap, the staff held themselves to the following rules:

- The entry must be written as a Python 3 expression that evaluates to a classifier function that takes in a Table row and outputs one of two reasonable values corresponding to genre: it can be “Country”/“Hip-hop”, 0/1, True/False etc. (a “Table” row is essentially a NumPy array, and is part of the software package created for the course)

- You may assume

numpyhas been imported asnp, and nothing else. - You may not use any file I/O.

- You may assume Python environment variables are set as needed at runtime (within reason).

- The entry must be no longer than 140 characters

Ah, yes, the Twitter classifier challenge. Or Tweetifier challenge, if you will. This turned out to be as silly as you might imagine. Ross details a variety of amazing entries, and some are remarkably concise. The requirement that the algorithm and the model have to fit in the tweet seems particularly challenging as you are not allowed to call into scikit-learn (importing scikit-learn would waste too many characters!). Of course, the main secret sauce is that Python3 and Twitter both support Unicode, so you can actually cram 2800 bits of information into a tweet. Who knew?

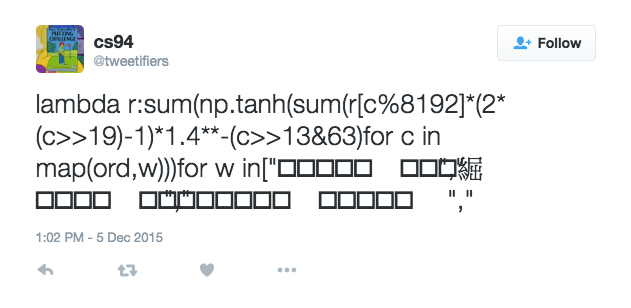

Go read Ross’ piece to find out what algorithm wins (I’m sure the seasoned folks out there can guess without looking, but it’s still fun). Spoiler alert: it’s not a deep neural net. Deep nets are unsurprisingly difficult to encode in 2800 bits. But unphased by this challenge, fellow TA Henry Milner gave it his best and came up with this two-layer neural net:

Editorial rant: I tried to directly paste the Unicode in a code block, but Jekyll seems to hate this. Jekyll is really a pain in the ass. But if you follow the link, you can actually run this in Python3.

In his words:

I used a 2-layer network with tanh activations (since “np.tanh()” is very short) and the second layer fixed at the all-ones vector (since I didn’t have space to encode and decode 2 separate parameter vectors, and “sum()” is also very short). The training objective was the hinge loss plus L2 and L1 regularization.

I trained with batch stochastic gradient descent using Theano. (After the training objective stopped changing, I chose the best model I’d seen in terms of held-out accuracy, which is another kind of regularization.) I used iterative soft shrinkage for the L1 term to ensure the weights were actually sparse, though it’s not clear that works well for neural nets.

I encoded the weights as key/value pairs: Each 20-bit Unicode character uses 13 bits to encode the index of the feature for which it’s a weight and 7 bits for the weight. The magnitudes of the weights turned out to be roughly uniform in log scale, so I encoded them with 1 sign bit and 6 magnitude bits. This is a lossy encoding of the weights, but it didn’t turn out to increase the held-out error, so that seemed okay. I fiddled with the L1 penalty until the resulting model was small enough to fit in my tweet.

This is clearly the future of machine learning.

You can find more “source code” for tweetifiers on twitter. And Ross has released the training and holdout sets so you can get grinding on your minimalist tweetifiers.