In order to get a grasp on what makes optimization difficult in machine learning, it is important to specialize our focus. Nonconvex optimization is so general, and what makes deep learning hard may be completely different from what makes tensor decomposition difficult. So in this post, I want to focus on deep learning and take a bit of a controversial stand. It has been my experience, that optimization is not at all what makes deep learning challenging.

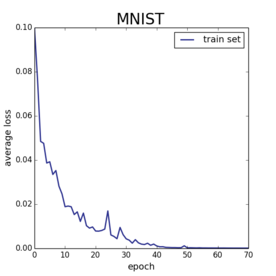

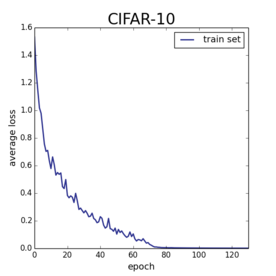

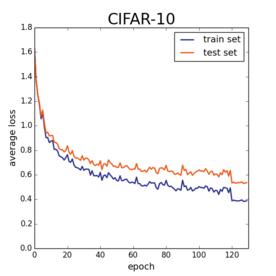

Look at these plots.

On the left I show the training error on everyone’s favorite machine learning benchmark MNIST. Here I trained a version of LeNet-5 with 2 convolutional layers and one fully connected layer. I used SGD with a constant stepsize. On the right, I show the training error on CIFAR-10. For this task, I used a bigger conv-net based on Alex Krizhevsky’s cuda-convnet model. In both cases, I am training using the soft-max loss, and after a sufficiently long run both of these models converge to zero loss. But the soft-max loss is bounded below by zero, so this means I am finding global minima of the cost function.

Now, I’ve been hammering the point in my previous posts that saddle points are not what makes non-convex optimization difficult. Here, when specializing to deep learning, even local minima are not getting in my way. Deep neural nets are just very easy to minimize.

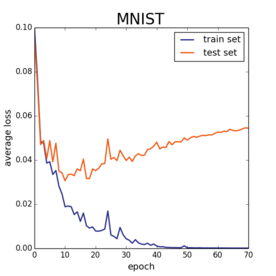

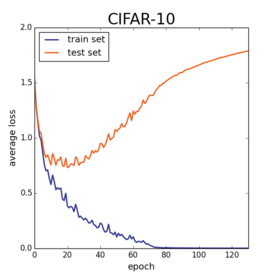

Of course, at this point, my machine learning friends are yelling at their screens, “dude, what does the test error look like?!?!” For the uninitiated, both the MNIST and CIFAR10 benchmarks ship with two sets of data points. There is a training set of examples from which you squeeze out every bit of information. And there is a test set which indicates how well your model will extrapolate to unseen data. Here are the same plots as above, but now I’ll also plot the loss on the test set.

The test error starts climbing upwards well before the models hit zero train loss. And there is nothing surprising about this. If one picks a model with enough parameters, you can (and will) overfit like crazy. The challenge in machine learning is attaining small training error quickly and efficiently while still generalizing to unseen data.

These plots suggest that our worries about optimization are misplaced when it comes to deep learning. Finding global optimizers is trivial. But finding models that generalize well is much more subtle. To get good performance on the test set, most of our efforts have to be devoted to forcing deep models away from optimal solutions. If I just take the exact same CIFAR-10 architecture, but I turn the learning rate down by a factor of 10, add a bit of $\ell_2$ regularization, and reduce the learning rate by 10x at epoch 120, I get this plot.

Not bad! The loss on the training set and test set track each other rather nicely.

I know this is obvious to most of you reading this, but it’s important to emphasize that the tradeoff between optimization and generalization is not unique to deep models. Understanding this tradeoff is the core technical challenge of machine learning. Even when we have linear models, we can find good models with very small empirical risk. Indeed, this was the whole point of the sparsity craze of the 2000s. If you have an infinite set of models that achieve zero empirical risk, the mantra in sparse optimization is to pick the one that is simplest. Depending on the specifics of the problem, simplest could be sparsest, lowest rank, or smoothest. It is often the case that one can find a simple model that fits the data exactly but still makes high quality out-of-sample predictions. But understanding how to balance data fidelity to model simplicity is always the challenge.

I want to be clear that I find the fact that we can overfit to the training set with a neural net and still generalize to be a profoundly interesting phenomena. That we can train crazy hundred layer ResNets and get near perfect accuracy on ImageNet is an amazing breakthrough. Why is it that stochastic gradient descent with a few bells and whistles is able to discover models that generalize so well? Moritz, Yoram Singer, and I tried to investigate this from a theoretical standpoint, but our theorems are far too pessimistic to fully explain what we see in practice. It remains a fascinating open problem to understand why neural nets are able to generalize, and I hope that future work is able to provide reasonable guides to the practice of building complex models that generalize.